An Underrated Tool for

Composing in Minor Keys

Minor keys. We know ’em, we love ’em. Sad, mysterious, melodramatic, sometimes epic or bittersweet. Minor keys are pervasive in nearly all styles of Western popular music, including but not limited to rock and metal, jazz, EDM, and video game and film score.

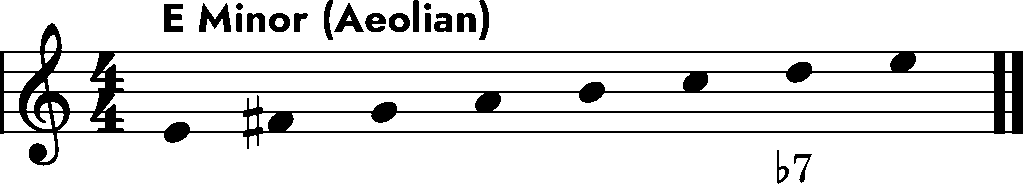

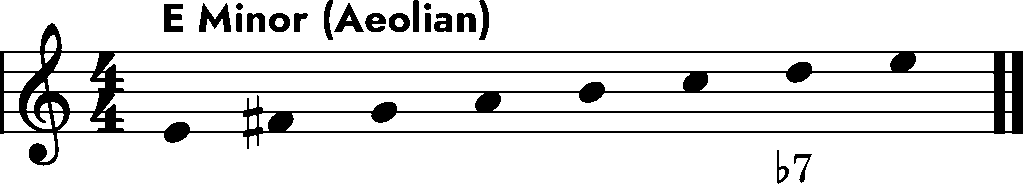

If you’ve written music in a minor key before, you’re almost certainly familiar with the Natural Minor or Aeolian scale. It’s a beautiful scale with a dark, ghostly sound, and it’s sort of the “default” minor scale for most Western musical idioms.

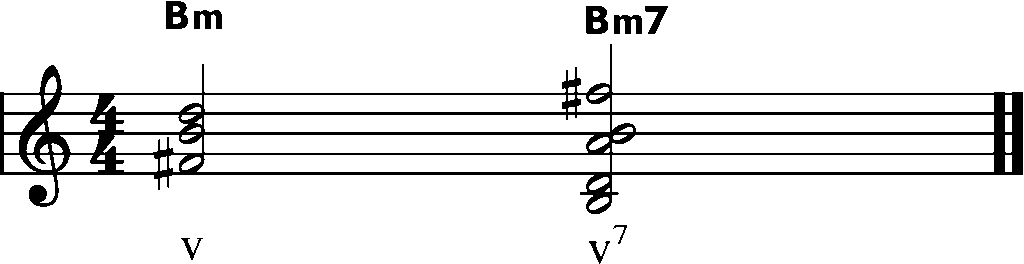

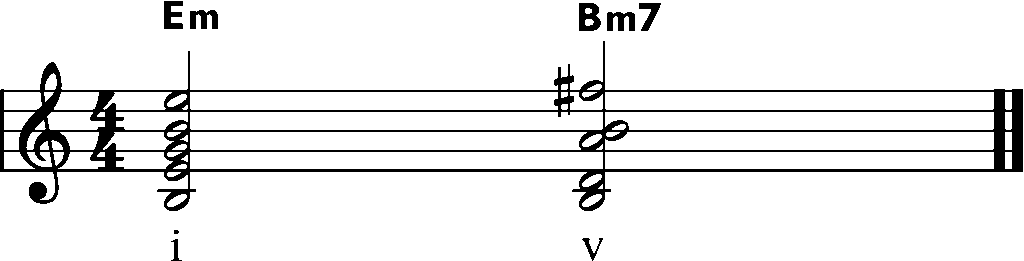

But if you’ve written Aeolian-based music for long enough, you’ll know that it has one small drawback: the scale’s flattened seventh degree means that the chord built on the fifth scale degree is a minor chord (or minor seventh chord), as seen above. Of course, this fact is one of the reasons the scale sounds the way that it does, so I wouldn’t call it a flaw, but it also means the diatonic five-one relationship doesn’t carry the same strength of resolution as its major scale counterpart.

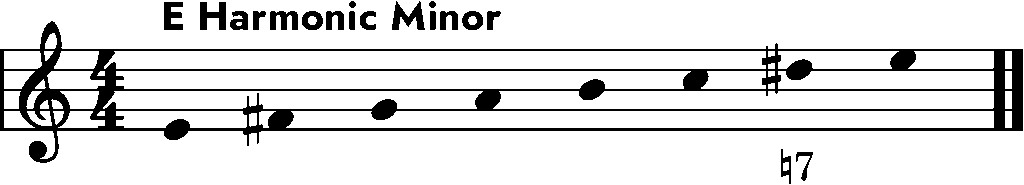

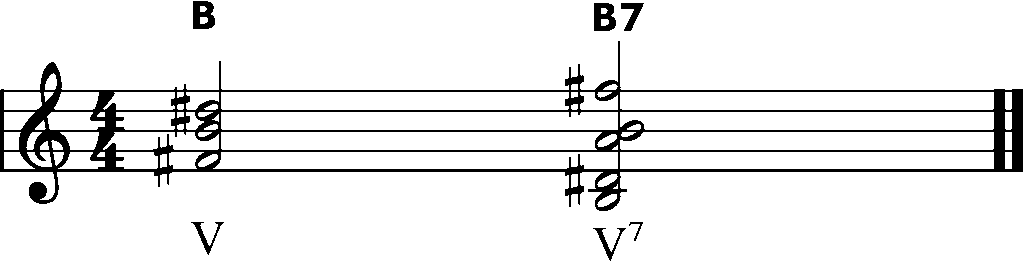

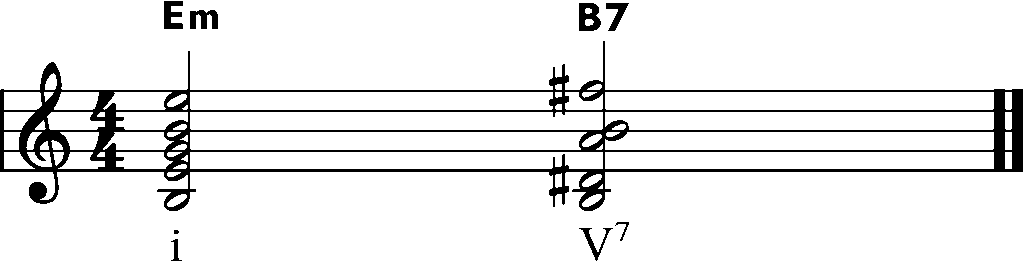

One common solution for creating that strong five-one resolution in minor keys is raising the seventh scale degree by a half-step, which introduces a leading tone (in this case, D♯) and changes the five chord to a major or dominant seventh chord. The resulting scale is commonly called Harmonic Minor.

Take a listen to the two chord shuttles or cadences below — the first comes from the Aeolian, and the second from the Harmonic Minor. Most will agree that when directly compared, the second has more “strength” of resolution, while the first sounds more “ethereal” or “ambiguous.” These qualifiers are further reinforced when used as compositional tools in real music instead of illustrative sequences of block chords like these.

The Harmonic Minor scale is commonly used both as the sole basis of a composition or in addition to the Aeolian, raising the seventh scale degree when heightened tension and release is required. The tension-release scenario is what we will be considering moving forward.

Hopefully, if all of this has made sense to you so far, you’re familiar with the concept of relative scales, specifically relative major and relative minor. Very briefly, relative scales share their “DNA,” having the same constituent set of notes, but get different names (such as “Major” and “Minor,” “Ionian” and “Aeolian”) because those notes are used differently and viewed from the perspective of a different tonic note/chord. (We’re going to bend this definition slightly in just a moment, but that’s the gist).

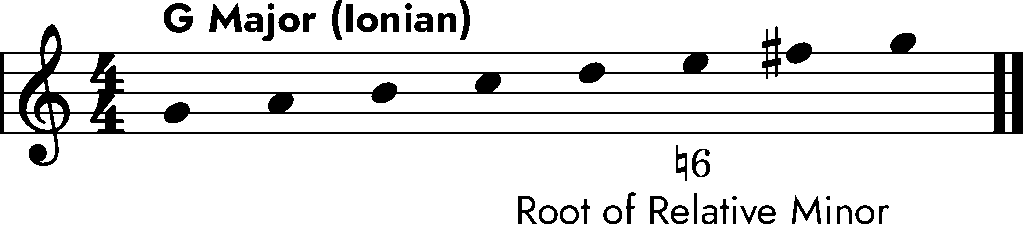

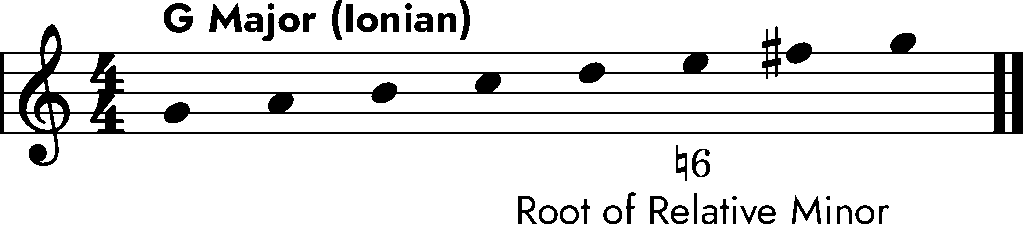

So far, we’ve been looking at the E Minor scale, so let’s take a quick look at its relative major: the G Major (or G Ionian) scale. Importantly, the sixth degree of G Major is the note E — the root of its relative minor.

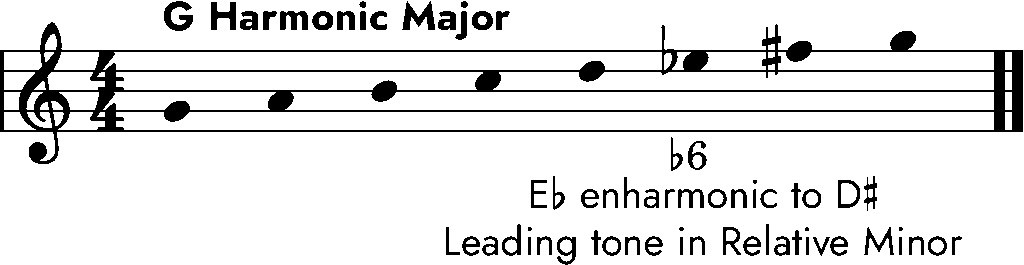

When we looked at the Harmonic Minor scale, we derived it by raising the seventh degree of the Natural Minor scale. The leading tone (D♯) created by that change is the primary driving force behind the scale’s ability to resolve in a classically “strong” manner. With that in mind, it stands to reason that some other means of introducing that same leading tone would likely produce a similar effect. Look again at the relative G Major scale above, and notice that if we lower its sixth degree, the note E becomes E♭, which is enharmonic to D♯, meaning they sound the same despite being named differently. We have once again created a leading tone for our minor scale. Neat!

This process of lowering the sixth degree of a major scale produces a new scale commonly known as Harmonic Major. When we do this specifically to the relative major of a minor scale for the purpose of introducing a leading tone, we create what I’m calling the Relative Harmonic Major, so called because it is built from the same starting note as the “normal” relative major scale.

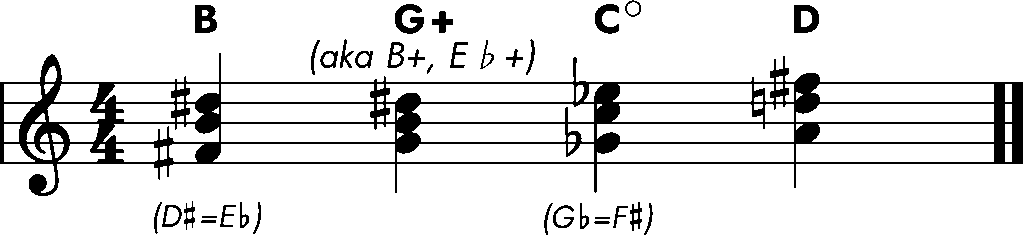

Let’s leverage this scale and its powerful leading tone to the relative minor by looking at some examples. To get us started, you’ll see and hear below the G Harmonic Major scale again as well as some common triads that can be derived from its notes.

If we take the notes of some or all of those triads (or, for that matter, any of the triads from the G Harmonic Major scale), specifically being careful to choose at least one that includes D♯/E♭, and play them over a B7 chord (or, in the following example, a D7 as well — something known as a backdoor dominant which is a different topic for a different time) in an E minor passage, we can create some very satisfying lines and melodies that resolve beautifully to an E minor chord. (To really get the Harmonic Major flavor, it helps to additionally choose one other triad that includes a D natural since both D and D♯ live in the scale). Take a listen and follow along with the sheet music below.

We can also use this Relative Harmonic Major scale to help us write interesting chord progressions in our minor key. All we have to do is create chords from subsets of notes in the Harmonic Major, and then resolve to our tonic minor chord. One such example can be seen and heard below.

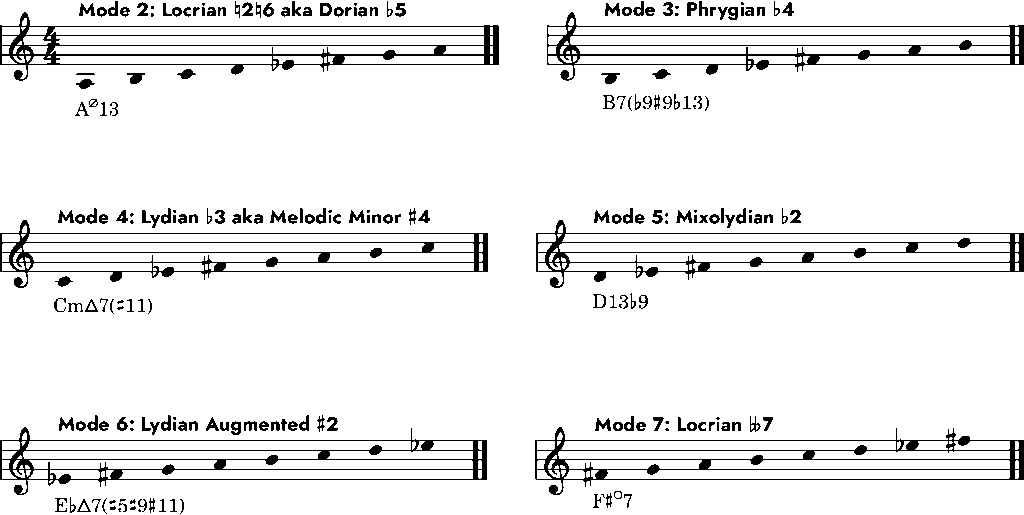

Next, I’d like to take a look at some more involved examples in the context of fleshed-out compositions. I’ll be pulling musical examples from my own band Caesura (debut EP coming very soon! 😇), but I’m certain that with a bit of effort you can find others out in the wild. First, though, let’s look at the modes of Harmonic Major. (If you aren’t comfortable with the concept of modes, it’s worth your time to study it in depth if you’d like a more complete understanding of where we’re going). When the Relative Harmonic Major is played over certain chords (seen below each staff in the following diagram) or bass notes, it can take on some very interesting or strange sounding qualities which can be leveraged to create unconventional colors and resolutions to a minor tonic.

Playing around with these modes is very fun, and I encourage you to do so. For now, we’ll be looking at my two favorites: Phrygian ♭4 and Lydian Augmented ♯2.

First up is Phrygian ♭4. In the example below, I’m leveraging this Harmonic Major mode over the B7 chords in measures 5-6 and 10-12. (0:04 in the audio is where the notation begins).

Alright, one more. This time, there’s still a bit of the Phrygian ♭4 sound, but I’ve included this example to focus on the Lydian Augmented ♯2 sound that you’ll hear in measures 6-8. In truth, there’s actually an assortment of Harmonic Major shenanigans going on this passage — I’ll leave it as an exercise for you to see if you can figure out what other modes are being leveraged! (This time, 0:03 is the beginning of the notation).

In summary, introducing leading tones to minor key compositions allows for powerful tension and release that isn’t possible with the Natural Minor scale alone. The most common method for introducing these leading tones is the Harmonic Minor scale, but it can also be accomplished with the less common Relative Harmonic Major, allowing for unexpected and interesting musical colors.

If you feel inclined, give it a try! Write some music with this concept or look for pieces where it might be found (I’d maybe start with video game music or early 20th century impressionist composers). I’d love to hear what you might find! 😊